The following is an entry in the “Free to Tweet” competition. It was submitted using the true identity of @PrezHuddleston (in accordance with contest rules*) via email on Dec. 15.

On March 8, 2011, I created a fake Twitter account for the president of the school I go to, the University of New Hampshire. Nine months later, @PrezHuddleston is bigger than I ever imagined.

In April, the account was the lead of an article that appeared in the Chronicle of Higher Education, USA Today and the Huffington Post. Dan Sinker, creator of arguably the most-famous fake Twitter account in history (@MayorEmanuel), was quoted saying of my account: “It’s a hard medium to stay alive in … People get bored of what you’re doing pretty quickly,” but he was wrong. In September, UNH’s branch of HerCampus.com named me a “Campus Celebrity.” In October, I did an interview with UNH’s student magazine, which branded me a “Twitter sensation.” Since early November, I’ve had more followers than the president’s real personal Twitter account, @MarkHuddleston – more than 1,400 in total.

There’s very little glory to it, I suppose – I manage the account anonymously. But my fake Twitter account means I live the first amendment every day. After all, when the campus magazine asked me “If you could tweet one thing to the real Huddleston, what would it be?”, I responded with the following.

“@MarkHuddleston: Free speech is awesome, no?”

But that was an understatement – the first amendment is more complicated than that. My fake account doesn’t just deal with the notion of freedom of speech – it’s a case study in the reach and limitations of it. Still unsure about that last bit? Consider this – in December 2009, a former UNH student was hit with criminal charges for doing what on the surface seems pretty much the same thing as me. According to the Associated Press:

[A UNH graduate] “was charged with criminal defamation for allegedly identifying himself as University President Mark Huddleston in instant messages and Facebook postings that included ‘inappropriate and suggestive comments.’ Sgt. Steven Lee declined to elaborate, but described the comments as crass and inflammatory.’” (Dec. 4, 2009)

Two years later, I’m impersonating the president too, but this time Huddleston is telling USA Today “I think we’re probably better off being a little more playful,” and appearing with a t-shirt I sent him in the university’s annual Homecoming video.

Which begs the question – what’s the difference between our situations? I embody everything that the First Amendment means in the 21st century and am a case study in how the amendment has been adapted – and is challenged – in this digital age.

Parody, and why it’s valuable

My preferred definition of parody comes from an article by Charles C. Goestch published in the Western New England Law Review.

“A parody is basically a criticism of the ideas and expression of another work. The essence of a parody is its comic or satiric contrast to the serious work. A parodist must copy and appropriate material from the serious work in order to establish the identity of the other work, to recall its characteristics, and to produce satiric effects which are often created by the ludicrous juxtaposition of serious and comic material.”

Parody, and its close relative satire, is one of the oldest forms of literary expression – employed by Shakespeare, Chaucer and numerous other authors. Parody is protected by freedom of speech, one of the five basic rights guaranteed by the first amendment.

The preservation of parody is vital. Parody is closely associated with satire, which employs tactics such as sarcasm and irony in order to express political and social criticism. At the most basic level, parody is meant to be entertaining. However, it also can be used to further the public discourse; It’s a creative and, often effective, method of broadcasting one’s opinion because it naturally attracts attention. The age-old cliché that jokes often have a little truth behind them is often true.

In a broader sense, societies and regimes that can’t take a joke generally aren’t the best ones to be part of.

My tweets: The good, the bad and the ugly

My account offers satire on the local, campus level. I tweet for a crowd consisting of UNH students, graduate and employees.

For instance, when there was a drug bust at an on-campus fraternity last month, this tweet went out out – its 71 retweets making it @PrezHuddleston’s most popular to date.

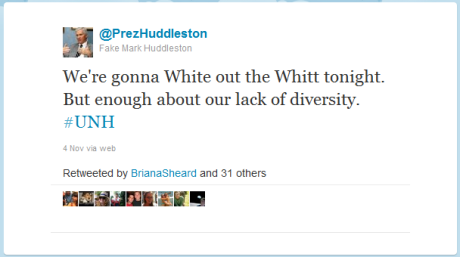

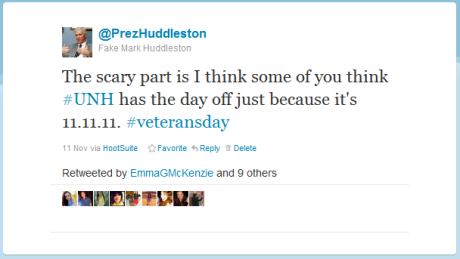

Some of my tweets reference practices that make the administration cringe. And others poke fun at UNH (White Out the Whitt, you might want to know, is when everyone wears white to UNH hockey games). And some of them critique the system.

The first amendment as it relates to parody: A history

The court cases often discussed within the subject of parody and free speech will always be relevant. 1964’s New York Times Co. vs. Sullivan laid out the standards for what classifies as defamation – the charge my predecessor was struck with. Defamation can only occur if the party in question knows the statement is false and proceeds with “actual malice,” or intent to damage the other person’s reputation in some way. Another frequently-cited parody court case – Hustler Magazine, Inc. vs. Falwell – upheld an ad that appeared to have evangelist Jerry Falwell talking about his first sexual experience, in large part because the average reader would have realized it was a parody. These historical cases (and many others) don’t quite deal with the particulars of a digital age, but they do differentiate between my account and what the other student did.

The 2009 case in which a former UNH student was hit with criminal charges for impersonating the president of UNH is one example of when people take things too far, and the First Amendment isn’t there to protect that. While we both impersonate(d) the same person, the 2009 case more closely resembles the age-old practice of harassment than the age-old practice of satire. The key differences were the failure to make it clear to the average person that it was parody and the use of inappropriate and suggestive comments (profanity and obscenity are not protected by free speech in certain contexts). Taken together, the two imply an intent to damage reputation, the critical element to a defamation charge.

Parody in the digital age

The Internet changed parody forever. Once, it was only possible to parody another’s product or literature; now, with social networking sites, you can essentially parody an entire person. That’s what I do on Twitter.

Each generation does some reinterpreting of the basic rights guaranteed by the first amendment. By determining exactly what constitutes free speech online, however, this generation will probably do more than most.

The Internet is where satire is going in the 21st century. Sinker, of @MayorEmanuel, referred to accounts such as his as “a new generation of satire.” Fake accounts on Twitter have been around for years. The majority of the parodies are written anonymously, as mine is, so as to make the portrayal seem as realistic as possible.

According to my research, anonymous fake Twitter accounts have been established for the presidents of American University, Brown University, Central Michigan University, Georgetown University, George Washington University, Harvard University, the Ohio State University, Penn State University, Southern Vermont College, the University of Colorado at Boulder, the University of Iowa, the University of Miami, the University of New Hampshire, University of Texas at Austin, the University of Virginia, Vassar College and Wesleyan University. Some universities take it better than others (those that haven’t been shut down or otherwise disbanded can be seen on this Twitter list).

The court case Reno vs. ACLU in 1996 extended the full protection of the First Amendment to the Internet. But things weren’t that simple.

Typically, discussions of the legality of parody are closely associated with discussion of the fair use doctrine, “a doctrine that allows copying from a copyrighted work so long as the appropriation is reasonably expected and not harmful to the rights of the copyright owner” (Goetsch – Western New England Law Review). That becomes legally murky. But because parody of a person doesn’t involve a copyright, we avoid that. Instead of copyrights, however, our discussion must be made in conjunction with discussion of online impersonation law too.

Unfortunately, that’s a murky world too.

Challenges to parody

In January 2011, the state of California made it illegal to “knowingly and without consent credibly impersonate another actual person through or on an Internet Web site… for purposes of harming, intimidating, threatening, or defrauding another person” (text of the bill here). There are similar laws that single out “e-personation” in other states.

The language is vague. In a blog post published when the law came into effect, Gawker asked: “What does it mean to ‘harm’ someone via online impersonation? How obvious does a satire have to be in order to avoid becoming a ‘credible’ impersonation?”

A 1980 piece published in the Albany Law Journal has an interesting way of looking at Gawker’s second point:

“A successful parody ‘must convey two simultaneous—and contradictory—messages: that it is the original, but also that it is not the original and is instead a parody.’ In addition to the second requirement, the parody must ‘communicate some articulable element of satire, ridicule, joking, or amusement.’ A successful parody minimizes potential liability under trademark law because consumers are less likely to be confused as to the source of the mark being parodied.”

Today, many fake accounts make it clear they are a parody from the start, as mine did, reflecting a growing willingness to avoid impersonation issues. Often, they are quite successful. However, it could be argued that that evolution did not occur willingly, and instead was necessitated by Twitter’s parody policy, which requires such explicitness:

“In order to avoid impersonation, an account’s profile information should make it clear that the creator of the account is not actually the same person or entity as the subject of the parody/commentary.”

Not everywhere appreciates this policy. The creator of @ceoSteveJobs (which had over 350,000 followers when it was shut down after the California law came into effect in January) argued that parody doesn’t generally have to label it as such – it is protected as long as a reasonable person would be able to recognize its satirical nature upon inspection.

The fake account for Jobs was shut down despite the fact that the creator was willing to add the word “parody” to the account’s Twitter bio after Apple, Inc. complained, and despite the fact that would be hard to prove that the parody was undertaken in order to harm, intimidate, threaten or defraud Steve Jobs.

Indeed, Twitter is a bit of a flip-flopper when it comes to its own parody policy. Two of Twitter’s most famous fake accounts, @MayorEmanuel and @BPGlobalPR, violate(d) this policy; they do not state anywhere on their profile that they are fake accounts. Three fake college president Twitter accounts – for Brown University, Georgetown University, and the University of Texas at Austin – have been suspended by Twitter, yet one of the most popular fake college president accounts remaining blatantly defies Twitter’s parody policy (it probably helps that the president it parodies, Columbia University’s Lee Bollinger, is a scholar on the First Amendment).

On a more recent note, Kansas Governor Sam Brownback (@GovSamBrownback) was heavily criticized for infringing on the First Amendment when his office demanded a teenage girl apologize for a tweet portraying him negatively (in a wonderful twist, he would end up apologizing to her). Yet there was no uproar when he complained about the fake account @sambrownback, which he managed to get shut down despite the fact that it said in the bio that it was fake.

Vagueness and double standards like this discourage legitimate exercise of the first amendment.

Why we need to avoid the “chilling effect”

The chilling effect is “the term used to describe the inhibition or discouragement of the legitimate exercise of a constitutional right by the threat of legal sanction” (yep … Wikipedia). The California law, along with similar laws in Texas and other states, are vague to the point that it is not clear whether parody for satire’s sake is appropriate, and thus discourage the perfectly legitimate exercise of a first amendment right.

Opponents of California’s law say that it is unnecessary, as there are already laws in place for fraud and defamation. The courts can easily evaluate the scope of these laws to apply to digital situations, making poorly-worded new laws unnecessary. New Hampshire, for instance, does not appear to have a specific online impersonation law, but was able to bring use the force of the law in the 2009 case when it was needed.

We have to realize that potential challenges are only beginning, and that the First Amendment is part of a living document.

The New York Times in June wrote about the rise of fake Twitter accounts as a political weapon, and noted “the growing prevalence of the anonymous accounts is raising questions about how to balance free speech and transparency in the fast-evolving world of online political communication.”

These questions will often be answered with legislation. Much of this generation’s work to evaluate free speech online will involve battling the chilling effect, when necessary. It is important to not let extreme examples of online impersonation to impact legitimate ones.

The First Amendment lumps together five basic freedoms – that of religion, speech, press, assembly and petition – in one line. Thus, they rise and fall together. If one freedom is weakened, the others will be as a result. All five are vital.

In the case of UNH, some have come to recognize the positive power of satirical accounts. By playing along, the president has become more popular – no longer merely a figure in the ivory tower – and a community has been strengthened by the ability to laugh at itself. Plus, in the words of the Washington Monthly:

“Sure, PrezHuddleston ridicules student government and gets angry at the Boston Globe for the newspaper’s low UNH coverage, but he also serves as a big advocate for UNH and urges followers to support greater funding for the university.

That’s almost like what a real college president does.”

I created a fake Twitter account for my college president, and now I live the First Amendment every day.

* In other words, this entry was not shared using an online alias.